At the end of November, I adapted a physical space game to online, with Gather.Town as my software of choice.

I first came across Gather.Town a lot earlier during lockdown as a potential tool for converting Trope High, my American high school themed megagame, to an online megagame, but I never got around to it. But later in the year I decided to run an adaption of Ivory Storm: a “deep game” that I’d designed for eight players while I was at university. I came back across the tool again and decided to take the plunge.

In this blog, I’m going to discuss the platform, its possible uses and its limitations. But if it’s something that you think would work for you, I wholeheartedly encourage you to create an account and have a play with it.

What is Gather.Town / Gather?

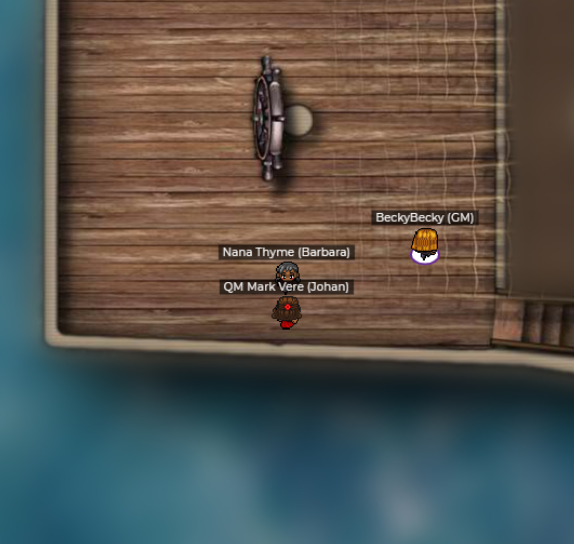

Gather.Town (actually Gather, but the URL of the site is gather.town) is a 2D map platform where users have an avatar they move around the space. When your avatar gets close to another user’s avatar, you immediately join a voice/video chat with that user.

Most excitingly, Gather.Town allows you to create your own maps. You can use their library of elements, such as walls, doors, floors, posters and sofas (the software was originally conceived as a virtual conference platform), or upload your own images and graphics. It’s also possible to interact with elements embedded into the map.

What is Ivory Storm?

To help you understand how Gather.Town works and how it might suit your game, I wanted to explain a little bit about the game I ran on the platform.

What is a Deep Game?

During my time at Durham University, some friends and I began developing “deep games”. I know now these were most similar to Nordic LARPs or Chamber LARPs – though I’m far from a LARP expert as it’s not really a hobby of mine. From what I understand, these LARPs are about creating a shared narrative, with a very high focus on roleplay, as opposed to more bosher-style LARPs with complex combat rules.

At the time, they were described to most people as “murder mysteries, but there’s not necessarily a murder”. The name was to contrast the other games we did as part of Durham University Assassins Society:”long games”, which took place over a longer period of several days or weeks, and “wide games”, which took place at a park or similar large area (similar to paintball games). “Deep games” went deeper into roleplay and immersion, was the idea.

Ivory Storm setting and mechanics

Ivory Storm, originally just called “the Pirate Deep Game”, was an eight-person game set on the pirate ship Ivory Storm. Players took roles as passengers or members of the ship’s crew, and the original eight characters were designed specifically for my eight friends who would be playing the different roles. I also had one person assisting me as GM for the game.

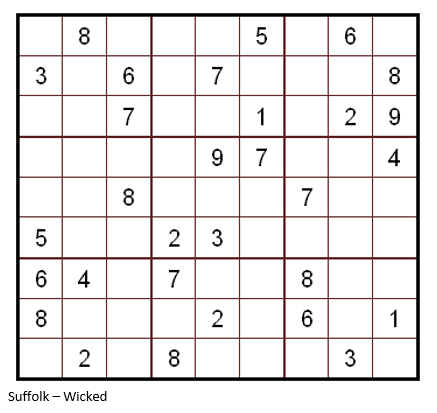

The game was held in our student house. It was specifically designed for the layout of the building, with mechanics utilising features such as the stairwell (you needed to go all the way up and down the stairs in order to change floor, to simulate the huge size of pirate ships). All of the rooms were cleared out ahead of the game, and players were encouraged to physically search various locations. Physical props were a thing, and a key mechanic was that each player had a bunk which could be “searched” – by solving a sudoku or tangram.

There were a number of mechanics that look completely different to anything I’ve personally experienced at a game since. Some for the better, such as the “sit and do nothing” mechanics that forced players to wait a predetermined amount of time before being able to do something (more on this later).

But there are some I believe have potential in other games. One example is “packets”, which are labelled envelopes which players opened in reaction to a trigger written on the outside of the envelope.

There were also mechanics that required players to pretend not to hear or notice certain in-game information. The most obvious example of this is SPEAK SPANISH, where if a player said that before saying something, other players had to pretend not to understand it – unless they could also speak Spanish in-game.

Benefits of Gather Town

I initially planned to use Discord for the game, with separate voice servers representing the different rooms on the ship. But there were a number of issues with this plan. Approximately three weeks before the game, I decided that Discord just wasn’t going to work and threw myself into Gather.Town.

Ability to “overhear”

Early on I realised exactly how important the “overhearing” aspect of the game was. The characters had secrets, and most had reasons to speak to at least one other person about them, but online communication is notoriously difficult for that sort of thing.

In Gather.Town, players can move their avatar into a room or closer to a group to start hearing what they were talking about immediately.

It also solved another issue, that having too many people in a group chat is hard to manage. On Gather.Town, it’s easy for players to just move away a little to chat to a smaller group, much like in real life.

Movement restrictions

Another drawback is the fact that pirate ships are damn big! On Discord, you can move from server to server with just the click of a button, and even with requirements to hop level-by-level or room-by-room, the feel wasn’t quite right.

On Gather.Town, player avatars had to physically traverse the space – which took some time!

Easy to learn – for designers and players

Due to the short timeframe, I had only one chance to choose an alternative piece of software, and I had to teach myself how to use it within that time as well. Luckily, Gather.Town has a very smooth learning curve. It took a bit of getting used to, in terms of some of the controls and types of tile, but overall it was pretty straightforward, and there were tons of materials available to help you get started.

And it’s super intuitive on the user side. You don’t even need to sign up for an account – just grant the permissions in your browser, and you’re off! If you’ve ever played a platform game before, the controls and format will be very familiar.

Interactive elements

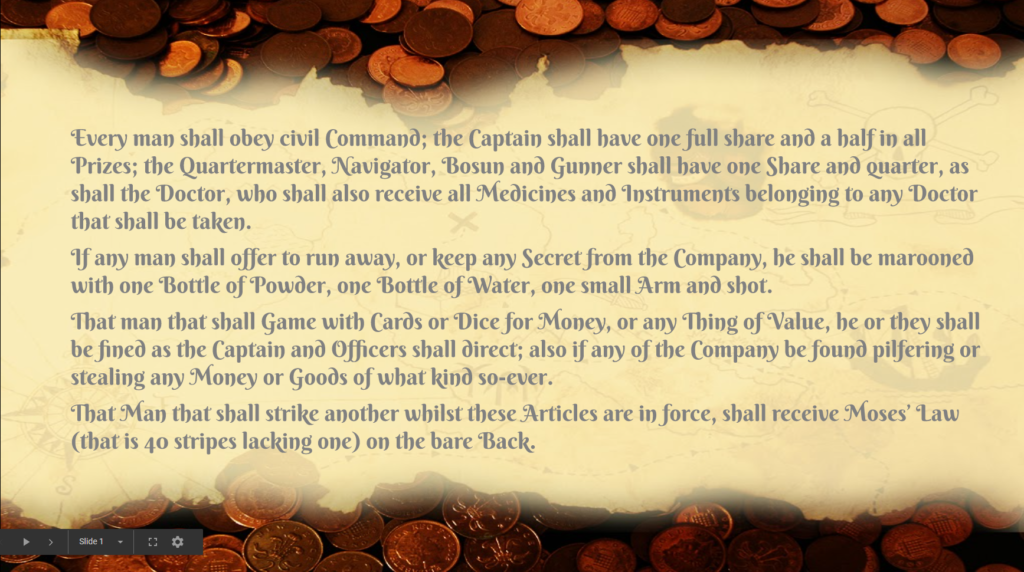

I didn’t know about this feature when I first decided to use Gather.Town, but one feature that really enhanced the experience was the interactive elements it was possible to embed within your maps. This could be website links, iframes, documents, whiteboards and even games. For simplicity, I went with embedding images or Google Slides with instructions on them. But with a bit more time you could get really creative.

You can also update those documents or images mid-game. I used this to make our poor invalid Peter get better or worse throughout the course of the game, meaning that players needed to keep checking on him!

Cost

Best of all, it’s free! Well, free for up to 25 users – though for any time period, and with unlimited interactive objects.

There are paid versions available, which start at £1 per user for 2 hours and a limited number of objects, all the way up to enterprise level options.

Challenges with Gather.Town

Obviously the platform isn’t automatically perfect for this use. Here are a few of the challenges that I came up against, and how I mitigated them.

Moderation

There is no way to teleport in Gather.Town. This means that if you are trying to track down a group of players to Control an encounter between them, you need to physically walk the length of the map (which, as stated, was huge). We got around this by also having a Discord server which contained Control channels, where myself and fellow Control Tim would sit. Other players could jump into a chat with us if they did need a word. Note that text-based chat was available – this was only an issue when verbal Controlling was needed.

Time-intensive

Despite the fact that it’s simple to use, it took hours to set up the map – creating each individual room, setting up walkable spaces, creating doorways using in-game portals… It was repetitive and quite challenging to keep track of, in terms of making sure that doorways worked both ways.

A way to mitigate this would be to design a map that needed fewer rooms, or combine rooms together.

New software to learn

Despite how intuitive it is, there are always issues when introducing players to unfamiliar software. Luckily it all worked fine for my players on the day, but it’s something to bear in mind, particularly if your audience isn’t super tech-savvy.

Lag

Probably the most significant issue was that a lag built up over the course of the 3-hour game. This affected loading of rooms, as well as the video chat function. Doing it again, I would build in hard-refreshes every hour or so to allow the cache to clear.

Future plans with Gather.Town

Fantastically, I think Gather.Town is also perfect for another physical game I hope to port to online – Trope High!

To start with, Gather.Town has built-in design elements for schools, as this is one of its original uses. This will make creating the map pretty easy.

I also have some fun ideas for replicating or even improving aspects of the original game. For example, in Trope High there was the concept of “Under the Bleachers”, where players could go to secret discuss things and know that other players were forbidden from eavesdropping on them. In Gather.Town, there’s a type of tile called Private Space, where you can create sections of the map that are self-contained in terms of conversation – making it physically impossible to eavesdrop!

I’d also like to take another look at Ivory Storm. Some elements of the game didn’t work well, such as the stand-and-wait puzzles (yes, unfortunately I had to keep a few of them in for this run). I do have a few ideas on this front, so watch this space.

In the meantime, I fully encourage any designer to go give Gather.Town a try. You don’t need to have an idea – just go have a play and see what’s possible with it. There might even be some new features – the user-side interface has been updated even since November when I ran my game.

Have you tried out Gather.Town? What game design ideas did it spark for you?