If anything has the biggest impact on your players’ experience at your game, after the particular role they’re playing, it’s their team. This can be seen as one of the easier aspects of a game to design, but it’s crucial to get right.

In this part of my design series, I’ll be looking at how to create the team structure for your game (if you’re having one).

There are multiple different factors that affect how your teams operate in your game.

- Are teams members fixed, flexible or dynamic?

- How many people are in each team? Are all teams the same size?

- Are there levels of command within teams?

- How are responsibilities / mechanics distributed within the team?

- Are there any solo players that operate outside teams?

- Is there intra-team conflict?

- Are there teams at all?

Let’s take a look at these one at a time.

Team Composition

In a lot of games, the composition of your teams is fixed and there is no way for you to leave your team or for someone new to join it. This is usually the case at games where you are playing a role rather than a person, e.g. Watch The Skies. That is because your role, e.g. Head of State for France, is not a named person, and if you were to retire, die or defect, you would simply be replaced, so it doesn’t tend to happen. This is normally the case where intra-team conflict is not expected or encouraged.

Team switches do sometimes happen in these sorts of games, primarily through wizard wheezes, but this can cause chaos if it means that certain mechanics can’t be covered by the remaining players in the team.

In some games, team structure is known to be a little bit more flexible. The idea of someone leaving a team, e.g. because they have married into another team, because they have been killed off, or because their alliance has formally changed, is coded into the setting and/or rules.

Finally, there are games where the teams are expected to change throughout the game, as alliances are formed and broken. Not many games steer hard into this – the best example would be Mirrorshades, where theoretically the Runner factions could have broken down and reformed, and/or adopted Freelancers formally into their teams. I was practically a member of the Specters by the end of the day.

Team Size

The size of your teams will depend on a lot of different factors, and there may also be some variation in team sizes across your game. Teams at most games are around three to five players in size, but they could be as small as one or two, or as big as ten or twenty!

A key factor to consider here is, how many different mechanics sub-games are your teams operating within during your action phase? You will normally want one player per major mechanic, e.g. combat, council, trade, plus a team leader. This is a good rule of thumb, even if you don’t assign players to particular sub-games.

Differing team sizes can be a good way to introduce asymmetry into your game. For example, at Watch The Skies, the US team, and sometimes China team, are usually larger than other teams, as a way to demonstrate their increased level of influence internationally. Or at Shot Heard Round The Universe, the individual colony teams all had four players, but the Imperial team had about ten!

If your teams have any sort of hierarchy or rigid alliances, you may find that you have several layers of teams, and that some of your teams end up very big indeed! For example, half of the players at The Pirate Republic were on the pirate team which had team-wide objectives, but they were split into smaller teams of three that also had their own objectives.

Team Command

There are three main ways in which megagame teams are commanded:

- Strict hierarchy – teams have sub-teams within them, and one person or team is in charge of all of the other teams on their side. This is common at operational military games such as Not Over By Christmas or Undeniable Victory.

- Flat team with leader – one player is designated leader of the team, and other players are all at the same level. There may be a VP, but they are not normally given any official deputy duties. Examples include Watch The Skies, Mirrorshades and Everybody Dies.

- Completely flat teams with no official leader – this is often only the case for one or two teams within games, although some games have it for more. Examples include the Free Beyond team at Shot Heard Round The Universe, or the runner teams at Running Hot.

Interestingly, the original definition of megagames according to Megagame Makers (on their previous site), put this team hierarchy front and centre (though with the caveat of “usually”). This is probably due to megagames’ origin in the wargaming hobby, which is most similar to the more hierarchical operational military games.

The majority of modern non-op-mil games take the form of a flat team with a leader, but before you default to this, consider if either of the other options work for you.

Also consider what sort of leader role you are having – are they in charge of the team with a definite level or power, or is it more “first among equals”? And how you are going to devolve decisions properly from the leader? It can be very easy for them to hog a lot of the fun if you don’t consider this.

Responsibilities and Mechanics

At a lot of games, each team member is assigned to one core mechanic. For example, at Watch The Skies, there is a Chief of Defence who does combat at the map, a Chief Scientist who plays the science and technology game, a Foreign Minister, who attends the UN and conducts diplomacy, and the Head of State, who leads the team (usually no specific mechanic). This is beneficial because it means that all players only have to be aware of the rules for their particular subgame. They’re also playing alongside the same players and facilitators all day, which means they can build up relationships.

At other games, there is no strict mapping for role to mechanic, and players are free to take any action they wish to do each turn. This can be useful for giving players variety and choice in how they hope their game to go; for giving teams the flexibility to focus player-time resource where they want it most, and to allow you to incorporate intra-team conflict without messing up a particular part of a team’s game. However, it requires players to learn a lot of different sub-games, and can leave players struggling if they do a mechanic for the first time half-way through the game.

And there are options in-between. Perhaps certain players can do some mechanics but not other ones. Maybe players need to commit to doing a certain action for an entire turn but can change action between turns. Team leads may have to assign duties to players, such as Military Commander, which they can reassign during the day but not necessarily at will. It may be that only certain players are recognised when they attend councils – sometimes through completely organic gameplay!

Or sometimes teams are formed by the mechanics they are doing – for example, the councils at Undeniable Victory.

Solo Players

Solo players can be very useful in a number of games – to represent small but important factions, or to provide an outside source of conflict or support for teams.

Generally these roles are very busy and can be very impactful on the game! However, casting solo players can be difficult, and it’s not usually recommended to put newer players in these roles. They tend to require players to be willing to insert themselves in situations and be pretty self-reliant when coming up with strategies.

Great examples of solo game roles include the Freelancers at Mirrorshades and the Red Priest at Everybody Dies. Press may also be a solo role, although this can be very challenging for larger and more complex games.

Intra-team Conflict

Again, this can be done in a few different ways:

- No intra-team conflict: teams are perfectly united. There are usually no individual character briefings (although there may be individual mechanical briefings). This is most common at games where players are playing functions or positions rather than characters. Examples include classic Watch The Skies,

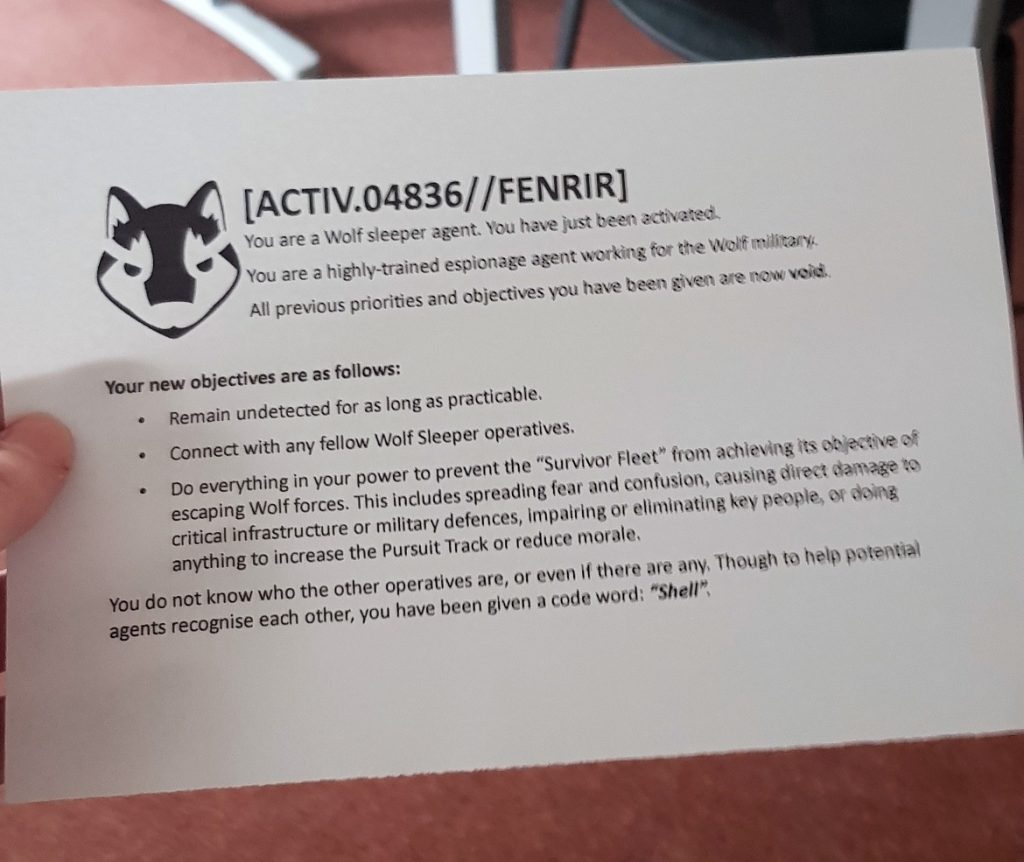

- Some intra-team conflict: some characters are specifically briefed to be traitors, to have specific opinions about other players on their teams, or to have motiviations that are at right-angles to, or directly opposed to, the team’s goals. Examples include Den of Wolves and Red Planet Rising.

- Teams in name only: teams are presented more as groupings. Characters usually have complex goals and may not expect to find allies on their own team. Examples include Everybody Dies and The Spanish Road.

Note that players will often do what they will – if you allow any amount of intra-team conflict within your game, it’s highly likely you will end up with more than you expected.

Are there Teams at all?

A very small number of megagames only have teams in the loosest sense of the word – or don’t have teams at all. For example, at Trope High, you could perhaps group the players into the Student Team and the Teacher Team. Or you could group them by clique. But they definitely weren’t teams in anything approaching the traditional sense of the word.

There are some who would argue this makes the game a LARP, but let’s not think too hard on that.

How Teams Affect Mechanics

Although this may be one of the elements of design that comes together naturally for a lot of designers, it can have big impacts on various parts of your game.

Firstly, the size of your team will impact how information travels across the game. If you have Team Time as one of your phases, you need to time it so that each person will have time to relay information to their teammates, make decisions, and be clear on what they plan to do next. This means that for a 4-person team, you probably don’t want to go under 5 minutes for Team Time.

Consider how the intra-team conflict will affect things across your team – the higher this is, the less players will trust other players to do things for them. If one player is responsible for collecting income, other players will doubt that they are getting all the income they are allotted. Similarly, if each player is assigned to a different mechanic, but the one assigned to trade is a traitor, not only will that team end up fairly screwed in the trade game, it may also be easier for the team to root out the rat.

If you are assigning players to specific functions but allowing team composition to change over the course of the game, or perhaps including player death where the Head of State may be replaced by other player, remember that this means that certain teams could end up short-handed, or with a totally inexperienced player (in a certain mechanic) getting involved a long way into the game. This can be disheartening for players.

Examples

There are a lot more interplays between team structures and mechanics. So let’s take a look at a few examples here, and talk about how their teams work.

Watch The Skies

Your typical Watch The Skies game is made up of 5-20 country teams. They usually have 4 player roles within them – Head of State, Foreign Minister, Chief of Defence and Chief Scientist. The US and China teams may have a fifth player, the VP. There is usually also an alien team (or multiple teams) of 8-12 players, and there’s usually a 3-6 player press team as well.

The teams are usually fixed throughout the game and won’t change in terms of composition. There is usually no intra-team conflict at all. Each player is responsible for a different core mechanic, and that isn’t likely to change over the course of the game. The team is led by the Head of State but is otherwise flat, and their power is mostly devolved by each player being wholly responsible for their own mechanic.

Arguably, the whole game is split into a humans vs alien team as well.

Everybody Dies

My own game, Everybody Dies (the original one), had nine different region teams generally consisting of 7 players each: the Lord Paramount, their heir or another family member, three Bannermen, a Maester, and a religious representative. There was some variation – for example, the North had no religious player, and the Crownlands/Dragonstone were a bit different. The maesters and the Faith players also had their own team objectives that brought together those players from across the different region teams.

The teams were pretty loosely aligned, and there was a lot of intra-team conflict. Some team members were all-out enemies! However, the Lord Paramount was most definitely the team’s leader, and held a lot of the team’s resources, to mimic the feudal society. In terms of mechanics, most players were free to involve themselves in most of the game’s mechanics, from map actions to diplomacy.

There were also some solo players, as mentioned – notably, the Red Priest, who in the first run was the only person to worship the Lord of Light across the entire game! The team of Bards were also operating on a fairly solo basis, as a medieval press team.

Undeniable Victory

The final game we’ll look at is Undeniable Victory, an operational military game. This was a two-sided game, with all players either on the Iraq team or the Iran team, although those teams were further broken down. There was the council, below that the army HQ, and below that the operational teams – ground corps, air and naval. The council had seven players, each a particular minister like Finance Minister or Defence Minister, while the HQ also had seven players, including Commanders for each operational team and the Chief of Staff. Individual corps teams had (I think) about four players each.

As you might expect from an op-mil game, there was a very strict hierarchy, with corps answerable to their generals, generals answerable to the Chief of Staff, and the Chief of Staff answerable to the council. And while the sides of these teams were totally fixed, it was not uncommon for players to get promoted to higher ranking roles/teams, or demoted, if they didn’t perform well.

Each player had specific mechanics to carry out, although again, promotions and demotions were possible. And there was a definitely some intra-team conflict – there were different factions within each team, such as Tikriti or Ba’ath parties within the Iraq team, and you were incentivised to promote your faction over others.

Summary

There are a huge number of factors that go into designing the team for your megagame. It might arise naturally for your design, but it’s worth considering what impact your choices will have on the rest of your design.

Try thinking about what sort of dynamic you are trying to create within your teams, and what structures have been like in games you’ve enjoyed. This will be a good starting point for creating the team structure for your game.

What sort of teams do you think work well at megagames – and what works less well?

Others in the “How to Write a Megagame” series

Part 1: Choosing Your Concept

Part 2: Logistics

Part 3: Scoping

Part 4: Mechanics

Part 5: Briefings

Part 6: Secret Plots

Part 7: Casting

Part 8: Teams

Part 9: Control and Facilitators

Part 10: Venues (coming soon)