It’s another Megagame blog post! Yes, this is my third Megagame in four weeks. Yes, I am starting to get a little Megagamed out…

What’s it all about?

This one was called Guelphs and Ghibellines (yep, I had no idea what that meant either), and was set in 13th century northern Italy. At this point in time, each major city in Italy is its own self-governing state, with the only real link being allegiance to the Pope. But the Holy Roman Emperor isn’t happy with his Empire being capped at the Alps, and wants to have proper dominion over all the City States. Some within the City States are happy for this to happen (or have been battered into being happy about it), and they are called Ghibellines. Others prefer the rule of the Pope and their independence, and they are called Guelphs.

Of course, that’s not the only dynamic at play. The Nobles have been in charge since forever, but recently the upstart Merchants have been bidding for more of a voice in their cities. They have money and contribute significantly to the economy, but the powerful hate their power being taken away from them.

And of course there’s the competition between the city states, with each vying to be the most powerful, the most prestigious, and the most awesome.

Prep

I was down to play another Control role, as the Milan Team Control. I was pretty excited about this – from my perspective as Map Control last game, Team Control seemed way less stressful and way more fun.

At very short notice, the sole Ghibelline from my team dropped out, meaning for the day I would be managing four Guelphs, three Merchants, and one unruly Archbishop.

The Guelphs on the left, the Merchants on the right, and that Archbishop in the centre…

Our briefings arrived only the day before – which was ideal for me as that’s generally when I read them. TC and I were staying at a friend’s, as the game was down in London again, and the boys spent most of the evening discussing tactics. TC was a Guelph in Bologna, and planned to make the most of his +2 in combat. Matt was from Genoa, a Very Modern City where they didn’t have such silly divides like Guelphs and Ghibellines.

Game Time

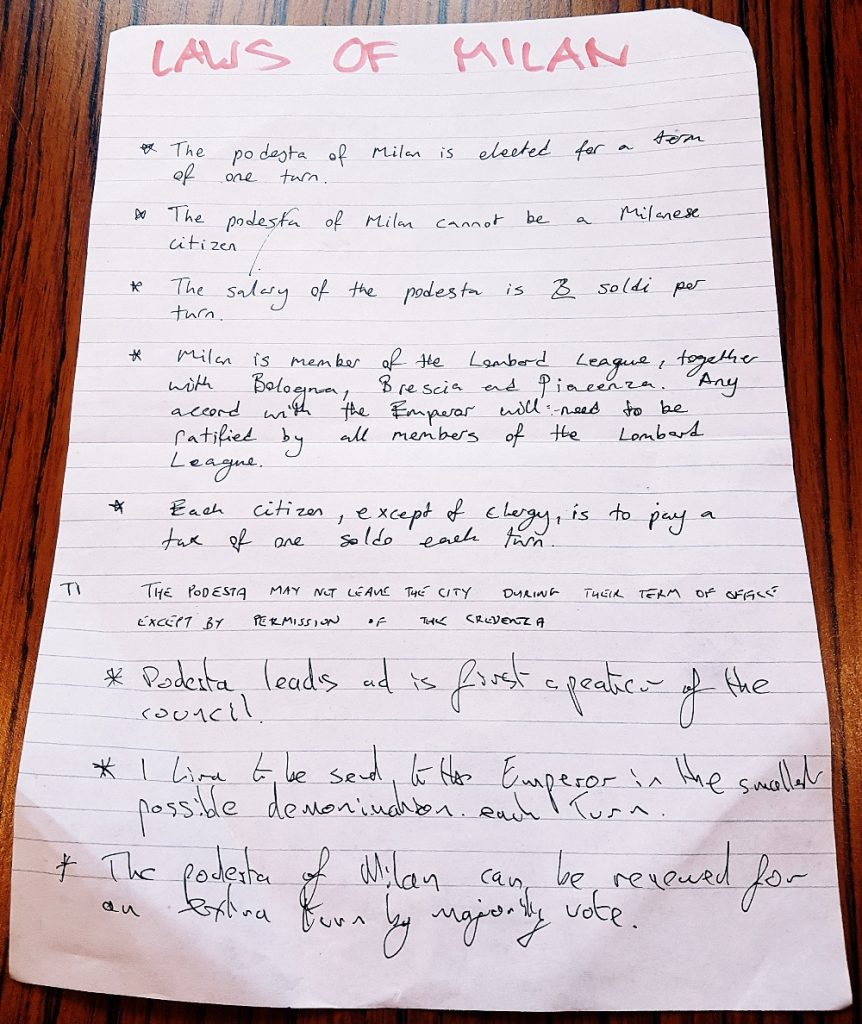

My team was a good mix of newbies, almost-newbies and veterans. Control was quickly seized by the Archbishop, who dominated the endless council meetings that were the majority of the game. The result of these council meetings? The Laws of Milan:

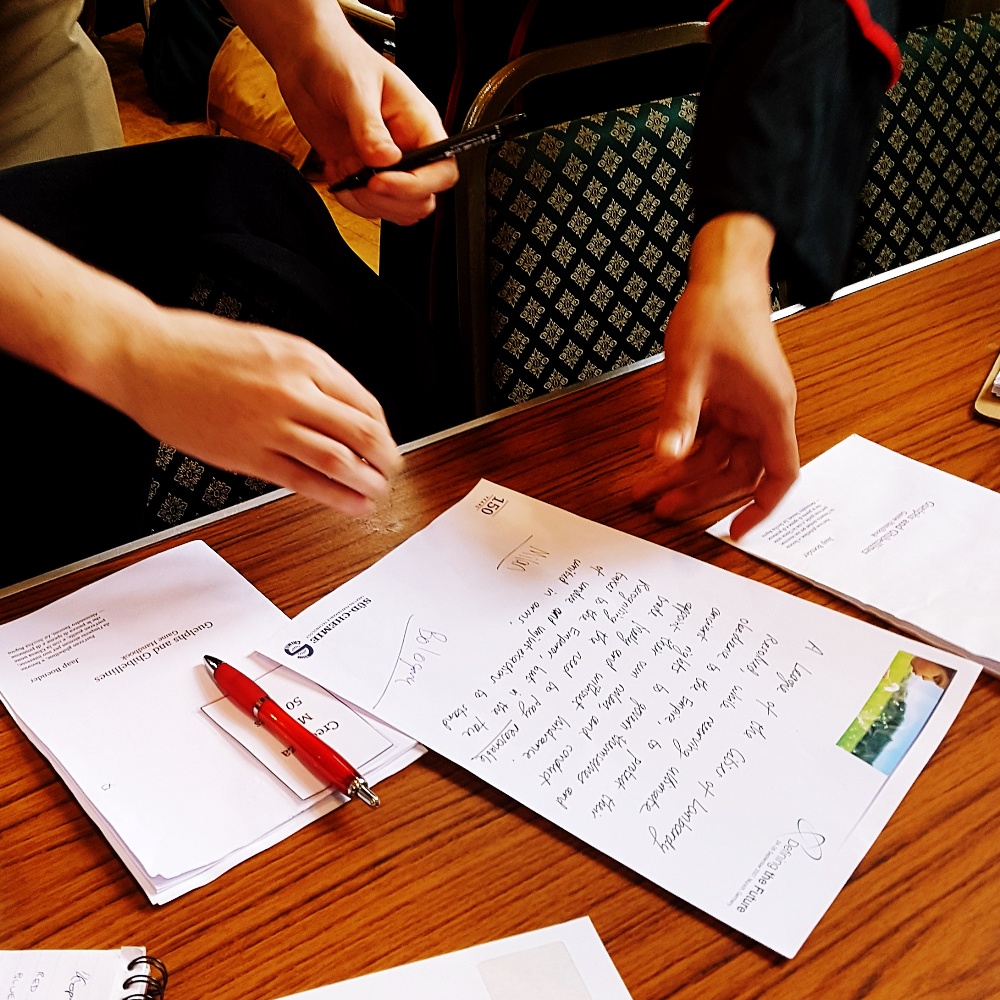

The main ambition of the Guelphs was to vie for power and position: by taking podesta positions (more on that later), by winning in combat, or by gaining money and power in their home towns. In a lot of ways it was a very loose-structured game, where players were free to make their own fortunes.

The merchants had a more difficult job. They were dying to seize more power and responsibility in the city, but were constantly called away to the map to manage their trade routes at the map. This meant they missed out on multiple votes simply by not being there.

Charitable Ambitions

The people of Milan were very giving. Very giving indeed, and even more so when they could do it publicly. Multiple citizens set up charities for no better reason than making themselves look good.

Two of the city’s charities were devoted to veterans, one to starving children. Each turn, quite a lot of the city’s income went directly into Control’s pockets for absolutely no reason. I felt quite sorry for some of them eventually, and gave them some extra combat units considering the sheer sum of money they were ploughing into nothingness.

Powerful Men

One of the standout aspects of the game was the need to find a Podesta (meaning power) each turn. This official ruled for a year and could not be a citizen of Milan. The salary was reasonably high, but the Council of the city had final say on whether they actually got paid or not – a vote could mean they went home with nothing.

Early on my team decided to slash the benefits the Podesta has. The salary was cut from three soldi down to two, and the player was forbidden from leaving the city (a.k.a. the table) for the duration of their rule. But many players around the room were vying for Podesta slots, so we never had trouble filling the gap.

Our first Podesta was from Venice. The Venetian team was another one of those Very Modern Cities, and was ruled by a Doge rather than a rotating series of Podestas (this didn’t turn out great for them in the end, after the Mad Doge was excommunicated then bought his way back into the church).

The Podesta from the second and fourth turns was a chap from Bologna. However, somehow our overwhelmingly Guelphic team got landed with a Ghibelline. He managed to stay very quiet on the topic of politics (so much so that he still got his pay both times).

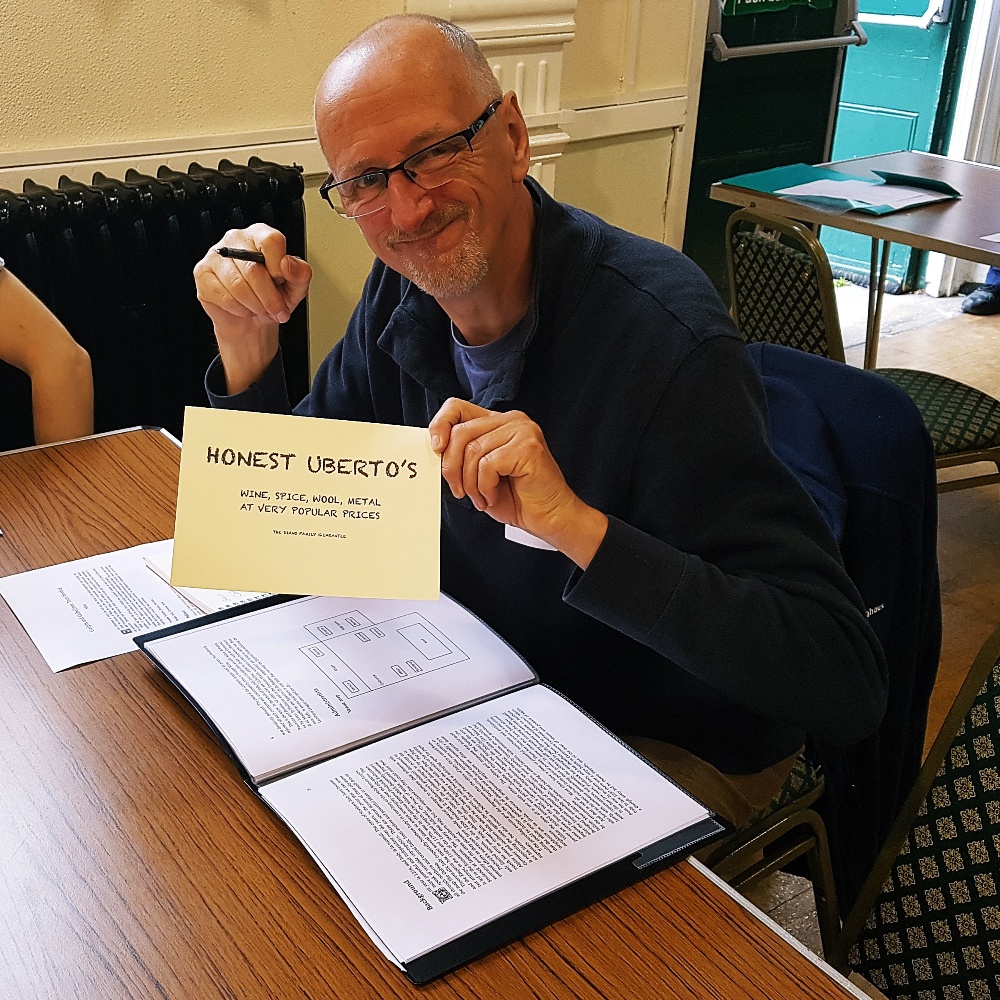

And the turn three Podesta was from Verona. None of these three Podestas did much to loosen the iron grip the Archbishop had on the city. Then came the Genoese.

He’s the forceful looking guy in the middle

Matt, my friend who had put us up the previous night, strode into the council meeting and took charge. Some may argue that he rushed the council into votes too quickly (and as a player, not an umpire, he was under no real obligation to hear every voice or treat every matter equally). But under his rule, the term length for a Podesta was lengthened to two years, just so they could keep him on again. The slighted Archbishop tried to argue that he shouldn’t be paid (like he’d have won that vote), but Matt just offered to waive his pay for that year, “for the good of Milan”.

The rest of the game saw either Matt or one of his fellow Genoese take the Podesta seat in Milan.

Milanese Skyline

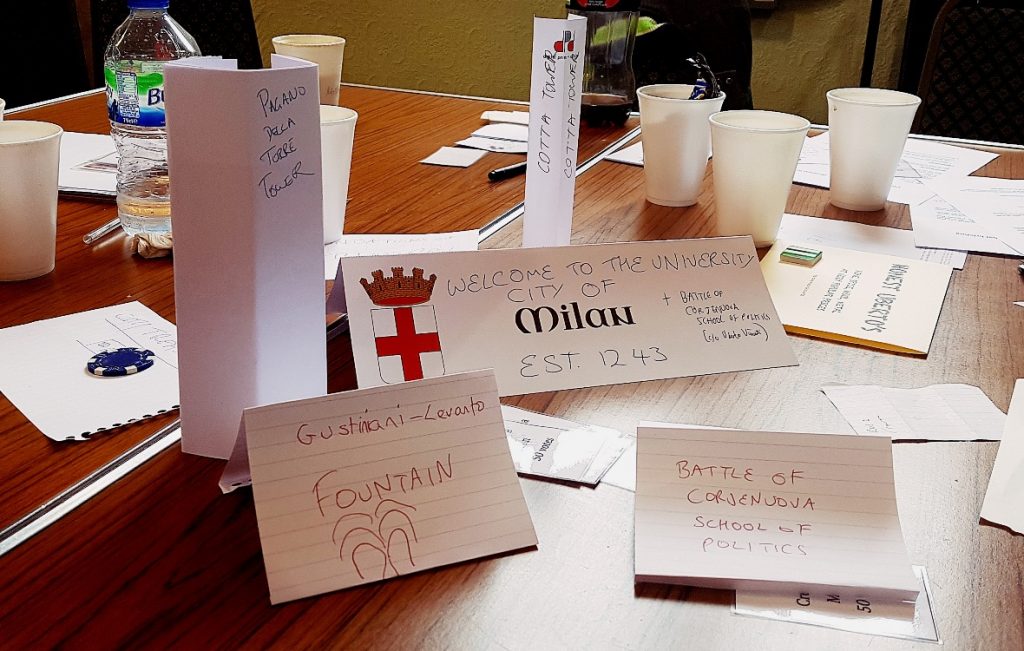

One of the biggest changes over the course of the game was the establishment of many notable buildings that, years from the setting, gap year students would no doubt marvel at the stunning architecture of.

This is how Milan looked at the start of the game:

And here’s how it looked towards the end:

This featured two towers built by players, a fountain dedicated to the two Genoese Podestas who reformed the city so remarkably, a very empty city treasury, and the fantastic University of Milan.

When my team first asked about building a university, I told them it would cost at least 30 lire – or 25 if they wanted the University of Lombardy Polytechnic. They’d almost given up on the idea, when they heard that Bologna were building an extension to their university. Amusingly this wasn’t actually true at that point. But Milan raised extra taxes and ended up spending 35 on it, and later an extra 15 on the “Battle of Corjenuova School of Politics”. I’m not sure why you’d name a school after a battle you lost, but whatevs.

The Rest of the World

Early on, Milan signed a treaty letting the Pope join the Lombard League.

This seemed to make sense – the Lombard League was a group of played and non-played city states united against the Emperor, and therefore mostly aligned with the Papacy.

Unfortunately once the Pope got in, he kind of took it over. He invited various other states to join (without the approval of any other members), some of whom definitely didn’t seem to be against the Emperor at all, and since any accord with the Emperor had to be agreed by all Lombard League states, it was easy for them to block treaties.

I’ll be honest, I’m not sure how the Pope and the Emperor worked things out, but apparently they did as they teamed up for… the Crusade.

“FYI we are at war”

Milan spent a lot of time arguing about whether or not to support the Crusade in Jerusalem. Saracen forces were invading the city, and the Pope was calling on the good Catholic nations in Italy to send reinforcements, money and troops.

The first resolution was to do… well, actually I’m not sure there was a first resolution. This was before the Genoese joined us, and the team spend so long arguing that the Saracens took over Jerusalem before we had a chance to help.

Later, under the Genoese podesta, we managed to raise some money to send to help with the war. There was much disagreement over what to do with the money – first we should buy troops, then ships, then troops again. In the end we just sent a fistful of cash to the Pope to do with as he may.

The peace the Pope made with the Emperor did include some semblance of taxes. “A reasonable level of taxes”, in fact. The Milan council decided that 1 lire a turn would suffice. They instructed me to take it over in “the smallest denomination coins, in a giant chest – and don’t forget to bring the chest back”. This involved a fair bit of miming, and 1 lire really isn’t much money at all. It was later discovered that Milan was the only City State paying any taxes to the Emperor at all…

Distrust

Even though the Guelphs vs Ghibellines conflict had stayed well away from our city walls, the other internal distrust was at an all time high by the end of the game – nobles vs merchants.

Close to the end, the nobles were pushing for a vote on whether to audit all the merchants’ books to root out any tax fraud. “How could they spend so much of the game trading, and have so little money,” was the cry heard.

When the merchants returned for the vote, they pushed to change it to a whole city audit. I charged them 7 lire for the privilege, then promptly told their Podesta that there was no tax fraud whatsoever.

Their taxes were just stupidly low! 1 soldi per player per turn (excluding the holy Bishop, of course), so even if the merchants had tons of money (they didn’t), the city had no rights to it at all!

Just as my furious nobles were planning to remove the legislation that gave the merchants a vote (which they’d have won, as there were more nobles), time was called on the game.

Aftermath

I was surprised that I didn’t enjoy being Team Control as much as I’d enjoyed Map Control. There just wasn’t tons for me to do – mostly I was telling players how much things cost. It definitely seemed to be a game where you got out what you put in, and I honestly couldn’t put a lot into it within my role.

That being said, the day was certainly entertaining, and my team did an awesome job of hating each other and everyone else in the room!

VIVA MILANO!

The next Megagame Makers game is Spanish Road on 16th July, where I will hopefully be Queen Elizabeth – come join in with the madness. Or if you can’t wait that long, The Jena Campaign is a Napoleonic war game in Huddersfield, where I’m going to be a French Chief of Staff.